Exploring Montana, August 22, 2014

It starred out pretty cloudy, with rain threatening. We lucked out, though and had a pretty good day exploring without getting wet.

We came across a small cemetery in the Garnet Range. There were only five buried in the Sand Park Cemetery, all hard-rock miners, between 1898 and 1914. According to interpretive displays at the entrance to the cemetery, little is known of them other than their names and when they died.

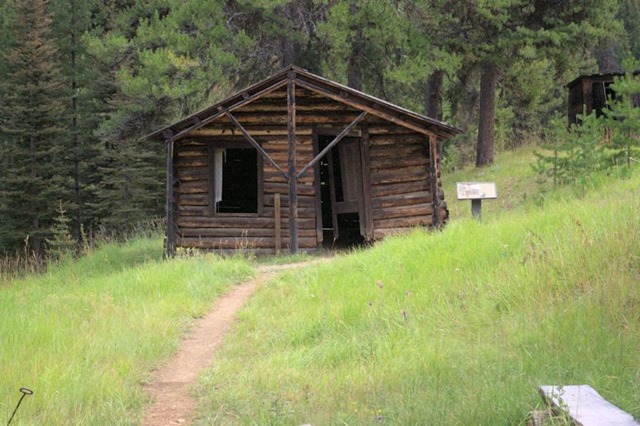

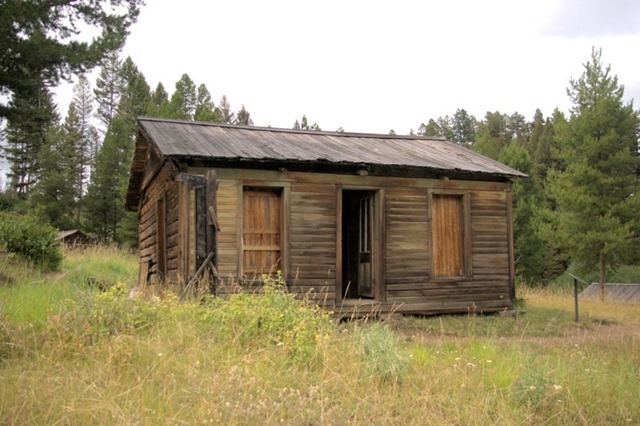

A little further down the road was an old 1940s fire warden cabin and, off to the side, the remains of an 1890s stage stop cabin.

We were surprised to see a wood stove, firewood and some meager supplies in the fire warden cabin. It looks like it’s set up as a short time emergency shelter.

|

|

A few more miles and we arrived at our destination, Garnet, Montana.

Mining started in the Garnet Range – named for a a semi-precious mineral found there – in the early 1860s, but it wasn’t until the 1890s that significant mining came to the First Chance Creek area. Between 1890 and 1895, 40 lode claims were filed in the First Chance Mining District. In 1895, a ten-stamp mill was built in First Chance Gulch and the town of Mitchell was founded, later renamed Garnet.

Road construction started that year eventually connected Garnet with Bearmouth and the Northern Pacific Railroad.

Shortly after the stamp mill was finished, a small “boom” began when a rich vein of gold ore was discovered in the Nancy Hanks mine. Miners poured into the small mountain town. Four stores, four hotels, three livery stables, two barber shops, a union hall, a butcher shop, a candy shop, a doctor’s office, an assay office, many miners’ cabins, thirteen saloons and a school with 41 students soon graced the town.

Eager miners and entrepreneurs built quickly, with no planning, resulting in a haphazard village where most buildings stood on existing or future mining claims. With the haste of boom-town construction, cabins and many of the commercial buildings had no foundations.

The boom was short. By 1900, most of the veins had played out. Five years later, many of the mines had been abandoned and the town’s population dropped to about 150. A fire in 1912 devastated the small business district and the US entry into World War I drew most of the remaining residents away to war-related jobs. Cabins were abandoned with furnishings still intact, as though residents were gone on vacation.

In 1934, gold prices were raised from $16 to $35 an ounce. With the higher price of gold, and new extraction and refining technology, a new wave of miners moved into cabins and began reworking the mines and dumps. The population, by 1936, had grown to 250 residents. During this period, a number of new cabins were built.

The onset of war in Europe drew the population away again. Wartime restrictions on dynamite made mining almost impossible. The post office closed for the last time in 1942.

Souvenir hunters soon began stripping the town after the last hardy residents died or moved away. More was taken than readily removed loose items. Doors, stained glass, woodwork, and even an oak bannister and spindles from the Wells Hotel disappeared.

To protect what remained, the Bureau of Land Management and the Garnet Preservation Society secured title to properties with the goal of protecting, stabilizing, and eventually interpreting the historic site. (Some property remains in private ownership.)

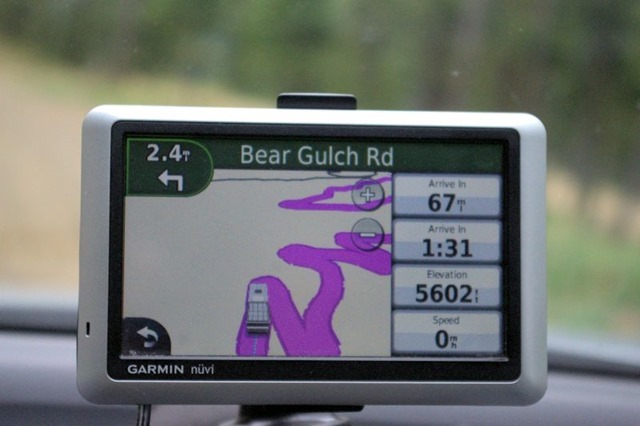

Leaving Garnet, we continued along the route we had been traveling. One of the volunteers had asked us which way were leaving. When I told him, he asked what we were driving. I told him, “a Honda CR-V,” and he said we shouldn’t have any problems. Apparently, some folks had driven over that part of the road in vehicles that weren’t appropriate. He mentioned that one guy in a Cadillac had “not been happy” with the road.

The route turned out to be another very curvy mountain road.

Except that it got very narrow, to the point that it would be difficult for two vehicles to pass.

And then we meet another vehicle – something like this one, maybe a few feet shorter, but just as wide:

They were coming uphill and we were going down. I don’t know what the narrow mountain dirt road etiquette is for this, but I figured it would be easier for me to back up that it would be for them. It wasn’t fun.

Once we were at a point where they could get past us, I rolled my window down and we told them that they should consider turning around when they got to a spot where it was possible, that the road didn’t get any better for several miles. They said that they had seen a sign saying “No RVs” but thought it was for a a different branch of the road. I think their accent was German.

Next up – Rained out.