Popular Science — April, 1937

Five weeks on the gypsy trail; 4,671 miles in a “rolling home”! That is the assignment I have just completed for the readers of Popular Science Monthly. To gather first-hand information about the amazing spread of trailer travel, my wife and I have driven through a dozen states, visited scores of trailer camps, talked with hundreds of men, women, and children who follow the Romany road in modern comfort.

According to the latest estimates of the American Automobile Association, 1,000,000 people are living in trailers. William B. Stout, the noted aircraft designer, predicts that, three decades hence, fifty percent of the people in the United States will reside in houses on wheels. During 1936, approximately 150,000 new trailers began rolling over the highways and, at present, nearly 700 manufacturers are turning out stock and made-to-order models.

Hunters are using trailers as mobile lodges, grocers are turning them into stores on wheels, prospectors are living in them as they hunt for gold, movie actresses are employing them as dressing rooms on location. They are featured in cartoons, in advertisements, in the movies, and on the radio. During the last New York automobile show, 1,200 persons an hour visited a single trailer exhibit. The house on wheels has come to the fore with a rush. And many people believe it has come to stay.

During our wanderings, we encountered bankers, farmers, fortune tellers, acrobats, surveyors, book salesmen, school teachers, evangelists,—all traveling in trailers and all enthusiastic about the life of a motor nomad. We saw trailers with awnings, trailers with porches, trailers with mountain scenes and waterfalls painted on the sides. We even met a bicyclist down a highway with a midget trailer trundling along. At one camp, we found a wealthy woman who had partitioned off a special room in her trailer for her colored maid. At another, we just missed a veritable Noah’s ark, a carnival trailer holding two grown-ops, two children, a police dog, a litter of puppies, and a lion cub! While we were on our trip, trailers from all over the country were rolling south. One evening, just at dusk, we pulled into a small camp in Florida and found five settled down for the night. One had come from Iowa, another from Michigan, a third from New York, a fourth from Ohio, and a fifth from Canada!

Most of the people with whom we talked were living on from twelve to fifteen dollars a week. Rent at a trailer camp including electricity, laundry facilities, and shower baths, runs from sixty-five cents a night to $1.35 a week. We heard of one family of five that started a trip with thirty-five dollars to cover all expenses except gasoline and oil. They traveled 15,000 miles, crossed seven mountain ranges, and reached home with seventy-five cents still in the treasury!

But let’s start at the beginning. When we commenced planning our trip, all we knew about trailer life was that it must be fun. For weeks, we pored over catalogues, talked to salesmen, interviewed people who had lived in trailers. We discussed the relative merits of Covered Wagons, Kozy Coaches, Vagabonds, Nomads, Zephyrs, Auto Cruisers, Travelodges, Silvermoons, Mayflowers, Travel Mansions, and Tally-Hos. We began speaking a language that none of our neighbors understood. We talked of parking legs, hitches, landing wheels, electric brakes, knee-action axles. We made large, middle-size, and small lists of “things to take.” We littered the table with maps, and read prospectuses that grew lyrical at the possibilities: “Visits to enchanted lands. . . . Freedom from cares and worries. . . . A silvery moon shining above, or a world of wonder passing by your window!” We were ready for trailer life. All we needed was the trailer.

There are three ways, we discovered, of getting one. You can buy plans and parts and build it yourself. Or, you can purchase a factory model, paying cash or buying it on the installment plan. Or, you can rent a trailer at so much a week. The rental rates range from thirty-five to fifty dollars, according to the size of the trailer. Usually, reductions are made for periods of a month or more. The agency supplies the license for the trailer. Sometimes, an additional fee of from ten to twenty dollars is charged for installing the hitch which attaches the trailer to the car. In almost all cases, the full amount paid in rent can be applied as part of the purchase price of the trailer-if you desire to buy it after you have tried it out.

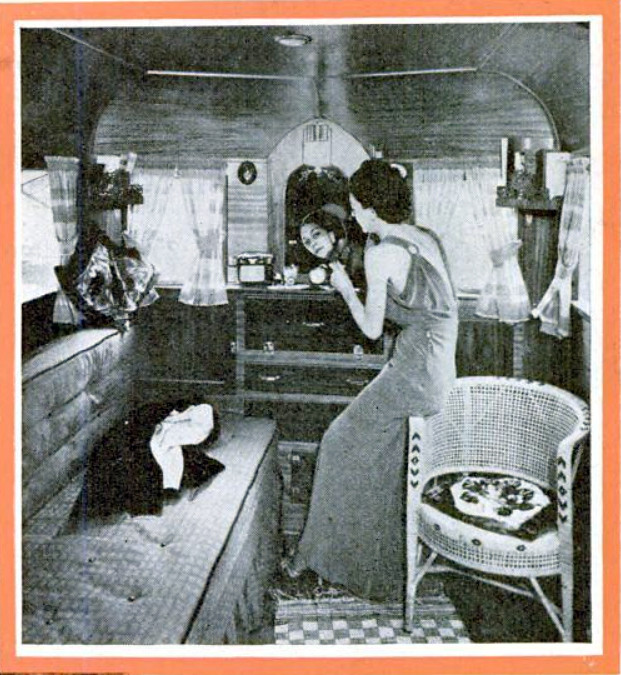

We found an infinite variety of trailers on the market. There are two-wheelers, three-wheelers, four-wheelers. They run the gamut from a $300 streamline “pup tent,” only a few feet long, to $5,000 ”road yachts,” thirty feet long and weighing 7,000 pounds. It is possible to get trailers with hot and cold running water, with vanity dressers, with water-closets, with telephones connecting trailer and towing car, with oil-burning heaters and gas stoves, with air-conditioning and hot-water-heating systems. Some are equipped with two-way radios, with electric refrigerators, with batteries charged by midget windmills on the roof. One even has a fireplace!

So many are the innovations and accessories designed for trailer use that at a recent convention of the Tin-Can Tourists, the national trailer organization, at Sarasota, Fla., a huge Ringling Brothers circus tent had to be borrowed to house all the exhibits. Some of the latest gadgets are folding steps, chemically treated garbage containers, and miniature electric washing machines.

Born of the depression, the trailer boom has spread to all corners of the country. It is keeping factories humming and inventors busy. Trailer enthusiasts now have their own magazine and, besides the Tin-Can Tourists, there is another organization, the A.T.A., or Automobile Tourist’s Association. Makers of equipment recently formed the National Coach Trailer Manufacturers’ Association. Summer conventions in the north, and winter conventions in the south, attract thousands of members of these three groups. During one gathering in Florida, 500 trailers pulled into camp on a single day.

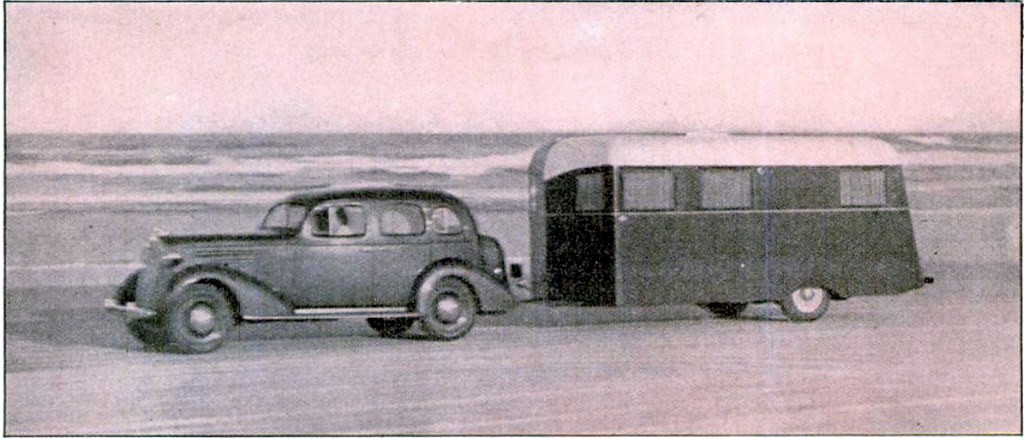

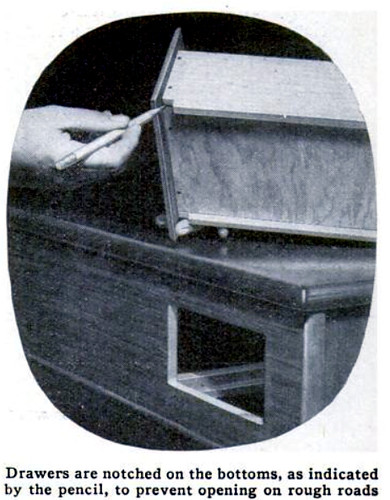

In the end, after considerable shopping around. we rented a $1,000 deluxe trailer from an agency near New York. Our home on wheels was nineteen feet long, six feet three inches wide, and seven feet nine inches high. It was trimmed in red and silver. The headroom inside was six feet, two inches. It contained an ice box, a toilet, a heating stove, a gasoline cooking stove, beds for four people, cupboards for dishes, closets for clothes, drawers for food and incidentals. Each drawer, we found, was notched so it locked itself automatically when pushed into place. This kept it from sliding out when the trailer struck a rough road or a sharp curve. To open a drawer, you lifted before you pulled.

Two kinds of lights illuminated the interior. Dome lights ran on current from the automobile battery, while regular lamps, operating on 110-volt current, were used in camps where electric connections were available. At the enameled sink, a pump drew water from a twenty-gallon storage tank beneath. The beds, as comfortable as you would find in any hotel, made up into seats for daytime use. Complete, the trailer tipped the scales at 2,100 pounds. It rolled along on two large, puncture-proof “doughnut” tires.

Two kinds of lights illuminated the interior. Dome lights ran on current from the automobile battery, while regular lamps, operating on 110-volt current, were used in camps where electric connections were available. At the enameled sink, a pump drew water from a twenty-gallon storage tank beneath. The beds, as comfortable as you would find in any hotel, made up into seats for daytime use. Complete, the trailer tipped the scales at 2,100 pounds. It rolled along on two large, puncture-proof “doughnut” tires.

For five weeks, the rent was $200. In addition, we made a deposit of twenty-five dollars to cover possible minor damages to the trailer while it was in our possession. At the end of the trip, we received twenty dollars back. Five dollars was deducted for a chimney cap which disappeared somewhere along the route and for photographic—developer stains in the bathroom.

Monday morning, we left the car to have the hitch installed. Late Wednesday afternoon, the dealer drove up the street, with a crowd of children trooping behind, and stopped in front of the house. My heart sank. The trailer looked as big as a mountain. Could I ever maneuver it through traffic?

That, I have discovered from questions asked me by friends since my return, is the first thing every beginner wonders. Half a dozen other questions always come out in the course of a conversation, so I will answer them here. The interrogation runs about like this:

Q. How about steering? Is it harder with the trailer attached?

A. No. You take wider turns, and you can’t cut in as soon after passing a car, but otherwise there is little difference. One thing you may notice at first is a slight pull-from suction every time you meet a car speeding in the opposite direction.

Q. Does it take longer to stop when you put on the brakes?

A. As a matter of fact, you stop quicker, because the trailer has powerful brakes of its own.

Q. Do you have any trouble finding a place to park at night?

A. Almost any tourist camp will take in a trailer. Country filling stations are often glad to let you park in the yard, if you buy gasoline the next morning. If you want electric connections, however, it is a good idea to plan your trip in advance so you will reach a regular trailer camp each night.

Q. Can you park on city streets?

A. Anywhere that there is space enough to get in and out. Usually, when you stop to make purchases, it is best to go beyond the main business district and to have either the nose of your car or the rear of the trailer at the corner of a street or alley. This keeps you from being blocked in by other cars parking close in front or behind. Always allow yourself all the room possible in maneuvering a trailer.

Q. Are any roads closed to trailers?

A. Only a very few boulevards and parkways in the biggest cities.

Q. Can you get on ferries?

A. It was our experience, during the trip, that any ferry that would take trucks would take trailers.

Q. How much does a trailer cut down your gasoline mileage?

A. It probably reduces it from two to five miles a gallon. During our 4,671-mile tour, we averaged eighteen and a third miles to the gallon of gasoline. A few side trips were made with the trailer left in camp. But, on the other hand, we were driving a new car that had just finished its first 500 miles.

Q. Is the trailer hard to attach and detach?

Q. Is the trailer hard to attach and detach?

A. Not at all. Anyone can do it in five minutes.

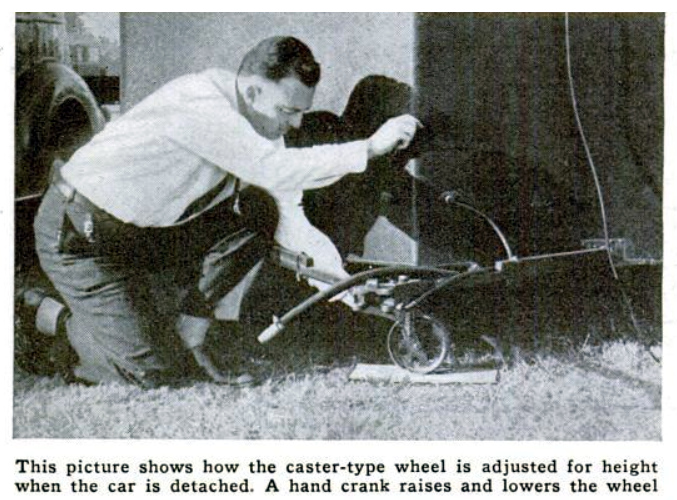

In fact, that was the first thing the dealer demonstrated when he delivered the trailer. He inserted a small crank in a slot, cranked down a post that supported a caster wheel on the trailer. Then he disconnected the electric wires and the hose for the vacuum brakes, and removed a spring clip and two steel pins and a block, hollowed out in the middle. This permitted the pear-shaped knob on the hitch attached to the car, to slide out, and the trailer and automobile were detached. In coupling them up again, the car is backed so the knob slides into place, the block, pins, and clip are slipped into their respective holes, and the connection forms a ball-and-socket joint which permits making relatively sharp turns to right or left.

It had grown so dark when I slid into the driver’s seat for my first and only lesson that I had to switch on the lights. Twelve hours later, I knew, I would have to steer through the streets of New York, the second biggest city in the world. I shifted into low and let in the clutch. We started slowly. I could feel the drag of the one-ton trailer. But, once we began to roll, we picked up speed rapidly. In getting started with a trailer, you stay in low gear longer, but after you get going you drive just as you would with the car alone. On an open highway, you can step on the accelerator and pass another car without the least difficulty. I talked to one man who drove across the Tamiami Trail, from Miami to Fort Myers, Fla., a good part of it at sixty-five miles an hour. I have heard of other trailers making eighty miles an hour along deserted highways.

Swinging wide on the turns and craning my neck from side to side, I circled the block twice and came to a stop, still intact. An accessory that helped, and is an absolute necessity in trailer driving, was an outside rear-view mirror. It enables you to see traffic approaching from the rear which otherwise would be hidden by the trailer. When the sun is on your right, you can often catch sight of the shadows of cars coming from behind before you can see the cars themselves in the mirror.

The most difficult part of trailer driving, the dealer explained, is backing. You have to remember to turn the wheels of the car in the opposite direction from the usual. This is because the car, when backing, acts in the manner of a boat’s rudder. Once you get onto it, he assured me, it’s easy. To demonstrate, he backed the car and trailer into the narrow driveway. Then he went away, leaving me assailed by many doubts.

We hurried through supper and commenced loading the trailer for the trip. We stowed away boxes of matches, bars of soap, dish cloths, knives and forks, paper plates, flash lights and extra batteries, a small broom, a garbage pail, and armloads of miscellaneous items. We stuffed the closets with old clothes and new clothes; we packed the drawers with bags of salt and sugar, packages of oatmeal and cookies, cans of soup and beans and meat and vegetables. It was easy to see why trailer travelers are dubbed “tin-can tourists.”

While this was going on, we were keeping open house for neighbors who wanted to see what a trailer looked like inside. Throughout our trip, we found this intense interest wherever we went. Chauffeurs and taxi drivers, farmers and storekeepers plied us with questions every time we stopped. Often it was difficult to get away from a filling station, because the attendant was planning a trip himself as soon as he could buy a trailer, and wanted to know all about the costs and other details.

Our maps had been marked and our route laid out. They would take us past places we had always wanted to see: Kitty Hawk, the wind-swept dunes where the Wrights first flew; Daytona Beach, where Sir Malcolm Campbell flashed over the sea-packed sand at 276 miles an hour; the Everglades, the Great Dismal Swamp, along trails followed by Daniel Boone, George Washington, Grant, Lee, and the Spaniards under Ponce de Leon.

As a final step, we checked over everything. There was a fire extinguisher, a first-aid kit, a carton of common drugs. The car was tuned up. All the spare parts were safely stowed away in the trunk. Our money was in travelers’ checks. Our automobile liability-insurance policy carried a rider protecting us with the trailer attached.

There were two last-minute bits of excitement. One was when we discovered a stowaway. In one corner of the trailer, Tarzan, the family kitten, had curled up and gone to sleep. The other was when we found—believe it or not—that we had forgotten the can opener.

It was ten o’clock when we finished our inspection and locked up the car and trailer. Everything was ready for the start. Before daylight, the next morning, our adventure would begin.