Outing, April, 1922

By Katherine Lafitte

There Must Be Something in It When a Woman Can Find Beauty in the Prairies, Joy in a Cyclone, and Fun in Mudholes.

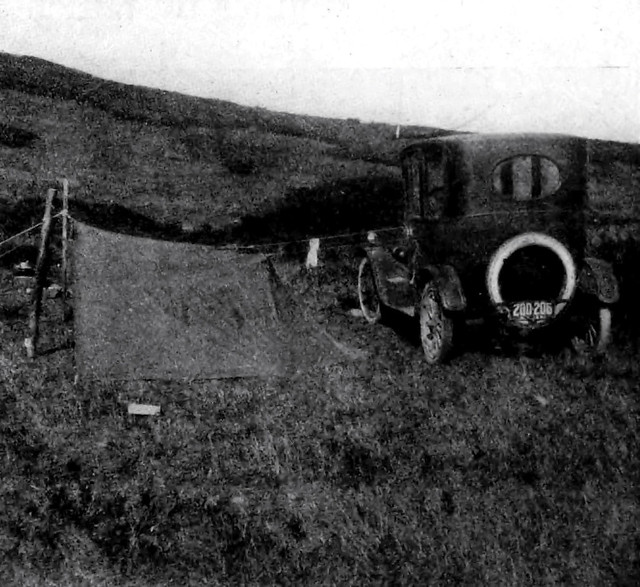

AMERICANS are seeing America a la automobile. A few go de luxe, curtained from the dust in great luxurious limousines, properly chauffeured, valeted and veiled. But the majority of us get into khaki and rough it—in Fords, Dodges, Buicks, Franklins, Mitchells, Maxwells, Coles—heavens! the list is too long.

“Free Camp Grounds for Tourists” is the Welcome Sign from Maine to California

We are bolting carriers to our running boards and rolling our own—blankets, tents, stoves, lunch kits, fishing tackle, packs and baskets, water-bags hanging before and behind, and tucked in on top the ever-ready camera, for scarce an hour goes by without bringing something worth snapping. And then, you know, there’s that sign, “Picture ahead. Kodak as you go.” One can’t get away from that—nor believe it always.

We’re taking the children along, so that we may stay as long and go as far as we like. And how the roads do beckon on! Something good around the next turn, what’s your hurry? Sometimes, if we counted fast as we slipped past, we found as many as six children in a car, and often a baby’s hammock swung from the top.

There were three in our car! Bill, Mrs. Bill and me. Not I—me. Four thousand miles seems quite a stretch, but we covered it in five ‘weeks, and we didn’t hurry, either. We settled down into a nice daily routine as easy as you please. Through thirteen states we bowled along, seeing America first. And the biggest discovery we made was her wonderful diversity. Of course we always knew it was there but we never really believed it before.

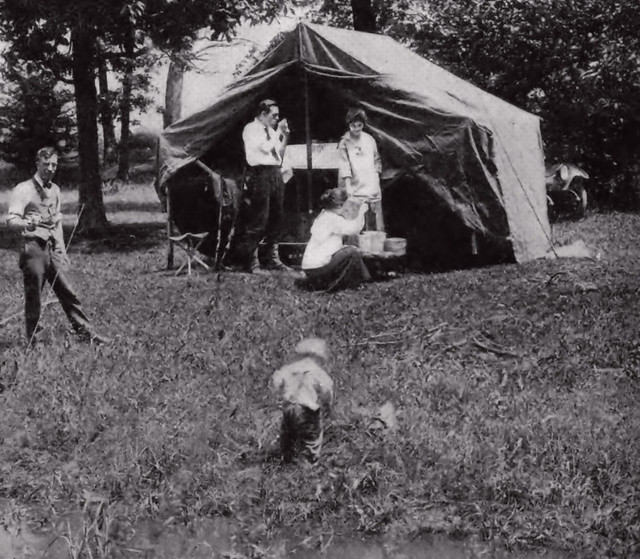

It’s great stuff, this cross-lots motoring. We learned, after the first hectic day or two, to pack our stuff so that there was room left for ourselves and got a camping system established that worked beautifully all the way across. About six P. M. we would begin to cast an eye about for a camping place, and within a few miles would find one. Sometimes it was a lovely open place by a river or a wayside spring; sometimes it was a kindly orchard; often a friendly little town. Most of these, in fact, had a sign hung out for us: “Free Camp Ground for Tourists,” That was always a signal for jubilation. There would be tables and benches. perhaps a brick fire-place, in a little grove. Occasionally there was a shower-bath—piéce de resistance——on the Long, Long Trail. Often there was a neat little shack with a stove. Fifty cars parked in the grove the night we spent at Aberdeen, South Dakota.

There was a retired army man from South Carolina, on a four months’ tour with his wife and the family pup; there were four tall and extremely dusty lads from New England, on motor-cycles; there were four Wyoming school ma’ams, driving their own car. There were folks from every corner of the U. S. A., and the big camp buzzed like a happy bee-hive.

“We’re taking the children along, so that we may stay as long, and so as far as we like.”

The little towns like the motor tourists, and met us with smiles. “Welcome” signs greet us at the front door, and “Thank you” speeds us through the back. And we like the little towns; we drank their chocolate ice-cream sodas all the way from Boston to Seattle, and bought our daily supplies of chops, milk, bread, butter, fruit, at their grocery stores. Sometimes an ice-cold watermelon. Yum yum, I’ll never forget a big fellow we had in a hay-field somewhere in Ohio; it was a blazing June day, and we did a swan-dive into that melon and came up smiling and juicy.

Well, to go back-—after we’d found a spot, then the stove was pumped up and set going (a dandy little gasoline stove called the Kamp Kook, which packs into 4 x 14 inches of space), then Mrs. Bill got the supper, while Bill and I made up cots and put the tent up.

Then there was supper, delicious in the open, and perhaps a walk, or singing and the ukelele around the camp-fire, and usually when the late sun went down we were peacefully snuggled into our blankets. Long, cool nights with no sound but the whispery, little noises of the woods, the hoot of a distant locomotive, or the hailing honk of another car.

Courtesy on the road, overdone. leads into a morass sometimes. But they’ll always help you out

Speaking of blankets, let me digress to advise any who are planning a tour—lots o’ blankets. We started out with a number that seemed quite sufficient, but ye gods! it sure gets cold after midnight when you’re out under the stars. Mrs. Bill likes lots of cover, and she raised such a howl that we punctuated the first part of the trip by blanket purchases. Towards the end our roll acquired such monumental dimensions that when we had crawled in we found it difficult to turn over.

A hard rain-storm caught us and the blanket-roll got wet. We slept “damply” for a couple of nights, but you don’t get cold easily when you’re living out-doors, and we grew browner and harder every day.

I mentioned America’s diversity. Diversity? Well, rather. Every one knows of the perfect roadways and the big cities and the prosperous farms east of the Mississippi, but all of us do not know the gold and purple of the prairies at twilight, or the spreading wonder of mile after mile of ripened and ripening wheat; the fragrance that greets the traveller through the vineyards of Ohio and Illinois; the smooth brown roads that cross Minnesota from line to line, a lake round every curve, and, beyond, the magic beauty of the vast grain ranches, each neat farm-house nestling in its dark green grove, and the big red barns, with their graceful, modern silos, making a generous splash of color in the landscape.

Everyone does not know the somber, compelling beauty of the Bad lands of the Dakotas, or how the sunsets in that strange, weird country surpass all other sunsets in their magificence. Nor yet the inspiration that grows when you, a mere speck between earth and sky, look down into a canyon that dwarfs the world you left behind you at the end of your winding road, and rims you in as in some vast cup from which you can only look up and be silent before the glory of the universe.

Changing, changing as you go. Sage-brush and giant fir-trees; flatness of the desert and snow crowned summits of the mountain sky-line; sands fine as powder and roadbed rocky as the cliffs on either hand. Five hundred miles where every hollow is the setting for a lake-jewel, and then a little city, brave amid its desolation, where one precious well serves the entire population.

There’s a wonderful camaraderie on the broad trails that crisscross America with their black and red, yellow and blue signs. Imagine four thousand miles over marked roads—we didn’t get lost once! Mohawk Trail and Yellowstone, National Parks Highway, Buffalo, Custer and Roosevelt—we followed them all. It’s never lonely on the trail; hardly an hour, even on the prairies, when cars are not coming and going, dusty heads leaning out to nod and smile, right

hands upthrown in hearty greeting, trail fashion.

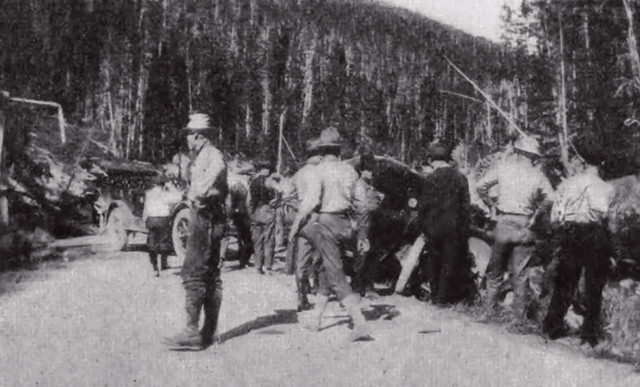

And we help each other. Stop to mend a puncture or investigate some unfamiliar sound issuing from the “innards” of your car, and your fellow stops to lend a helping hand. The man who passes by another who may be in trouble simply doesn’t belong, that’s all. Convention “kinder slips off” when you’re on the road, we pull each other out of mud-holes, or we lend an inner tube as far as the next garage, or we spare a pair of pliers or a gallon of gas. And when we camp, we hobnob over the campfire and compare notes—and cars. You’re the center of the universe when you’re hobo-ing in your car.

There’s a splendid exhilaration in the mountain roads climbing, ever climbing, when around each curve new beauties await you, and the car swoops over a rise and down the endless grades like a live thing glorying in the freedom or the high places. There’s a special thrill in every serpentine bend of the road that hugs the cliff-side, giving you a new respect for American engineers, and perseverance and ingenuity. Up and up and up, and then the Great Divide, with the waters turning westward, and beyond, as far as the eye can see, range upon range of brown and blue and faint lavender, as the distance paints the mountains, their sheer sides dropping into wooded slopes, and below that into brown rolling hills where the wild flowers amaze you with their variety and luxuriance.

We struck all sorts of weather. Coming out of Chicago, a driving rain-storm hurried us behind our curtains—I upset the entire car hauling them out from under the back seat—and sent hundreds scurrying from the lake beaches, Miniature cyclones chased us all the way across the Dakotas, usually catching us at camping-time. One evening we had our tent all ready for the night, dinner simmering nicely on the hot stove, when Mr. Cyclonette arrived on short notice. It must have been funny to see us hustling hot stove, dinner, tent and all into the friendly open school house whose pump we happened to be patronizing on that particular night. Mrs. Bill grabbed up an open cot, its canvas filled like a spread sail, and she was carried by the shelter of the porch, drifting like a derelict before the gale and yelling like an Indian. We rescued her, and she flopped on the steps. breath and hair-pins completely gone.

So we slept in the school-house that night, with the globe and the blackboards and the telephone and the moths ’n everything, and ate our breakfast off Teacher’s desk next morning! Mr. and Mrs. West, pioneers in that section, stopped to bid us welcome and furnished a pound of delicious butter and some cream. They told us that the district was suffering from a plague of grasshoppers which had wiped out a very promising crop of wheat in two short weeks; that on the heels of the grasshoppers had come the army worm, taking what was left, and that some of the settlers were packing their goods and leaving their ruined prospects behind. But that was the only place where we found such a condition.

When the wind-storm and the ensuing torrent of rain were over, we went outdoors. In the east lowering black clouds showed where the storm was travelling and jagged streaks of lightning blinded the eye. Suddenly, as we looked, the clouds in the west lifted, the sun dropped below them, and went about his business of setting with gorgeous pomp and circumstance. He flung his mantle of gold about him, and the wind carried it north and south beneath the purple velvet of the storm-cloud. He sent long splinters of light across the shivering prairies, touching as with a white spotlight the long line of telephone poles that climbed the hills beyond, until they shone like burnished silver against the blackness where the lightning played. And then, a rainbow drew its slender beauty across the sky, a tiara magnificent upon the brow of evening. The weird light lasted for about an hour, while we stood entranced and awe-struck, watching till it faded into Night.

Twice, along the road, a sand storm overtook us, borne in the teeth of the gale that threatened to overturn the car, but we held her nose into the wind and weathered through.

Among the Canadian Rockies, we buttoned ourselves in snugly just in time, as a hail-storm descended upon us. The hard white pellets fell so thick, so fast, so hard they hurt a hand outstretched, and in twenty minutes road and fields were covered white as snow; in another twenty the sun was shining serenely, and but for a bit of muddy going we were none the worse.

The day we climbed the Montana hills to Glacier National Park we almost froze. We put on all the wraps we had, bundled blankets about us and huddled down for warmth, but we faced a steady gale as we climbed, and began to think we had reached the North Pole instead of the Park. Straight off the glaciers came that wind, and the contrast with the preceding days across the plains was striking. You can imagine how glad we were to see the great open fire in Glacier Park Hotel, with its inviting circle of arm-chairs, and firelight playing on the many beautiful trophies that adorn the great lobby.

Oh, yes, the Park was worth that, and more. We met the rest of our party there, they having motored over from Seattle in a Ford that made the fifteen hundred miles there and back without even a puncture. There was a joyous reunion at the charming little station, and we stayed in the Park for a week, wandering among its wonders, most of which are easily accessible.

America on the trail uses everything from the finest and latest bungalow on wheels to the well-known and heartily-cursed pup tent of khaki days. Nearly three-quarters of the visitors to National Parks carry their own “sleeps.”

The boys hiked to their hearts’ content, climbing over Swift-current Pass and up to about 8,000 feet. They coaxed a marauding brown bear into a chalet at Granite Park, and bribed him with molasses to pose for his picture; and otherwise beguiled themselves while we of the gentler sex revelled in the gorgeous setting of our chalet on Lake McDermott, ringed round by towering peaks and dropping by way of three lovely cataracts into the river below.

We took the launch-ride up St. Mary’s Lake, to that sheer, stupendous giant, Going-to-the-Sun, a launch ride which is perhaps unequalled in the world for varied charm and beauty.

At the end of a perfect week we turned northward, and instead of shipping the cars over the yet unconquered Continental Divide, we ran up into Canada and ducked around the northern end of the range in the Waterton Lakes country. Lovely country that. too. There’s a little town in British Columbia, Fernie by name, where they have a camp-ground worth noting. A house, big stove, running water, cold and delicious, electric lights, tables and benches, fishing right at hand—some campground! And we had barely arrived when the publicity man of the Chamber of Commerce ran in to offer us the keys of the city or anything else they had. And no sooner had we finished dinner than we had even more distinguished guests, the Mayor and his Lady. Don’t over look Fernie. B. C., if you are rambling through the Canadian Rockies.

On our way down to the line, we passed through the site of that little buried city of Franklin. What a graveyard! Some years ago, the little mountain town was going calmly about its business at high noon, when suddenly half of the mountain looming above it fell, throwing its huge masses of rock for a mile and a quarter across the little valley, boulders bigger than the houses they crushed, damming the river at its foot, and forever obliterating the little town and all its people; one girl who was walking on a distant trail was the only survivor of the tragedy. There it lies, a mile square, and more, of broken limestone, indestructible monument over the many graves that lie beneath.

While we were in Montana, July Fourth, we climbed a range, mounting from one broad table-land to another, over roads which I refrain from describing (it suffices to say they were bum!), and ran spang into the great annual festivities of the Blackfeet Indians on their own reservation. Wasn’t that luck? A beautiful little city of tepees—honest-to-goodness tepees—down in a little green valley walled in by the mountains, and Indians gathering from every direction for the big celebration.

Think of seeing a real Indian parley-voo! Not movie stuff, but the genuine article, unwitnessed but by the few travelers who happened by that way. The Big Chiefs seated in a solemn circle, gorgeous in their blankets, feathers and paint. Real Medicine Men, and one revered old Medicine Woman who had fasted for a week in preparation for the ceremonies. A blind old man, his face a network of wrinkles, led to his place and worshipping the Sun-god with eyes

that had been in darkness for many years.

The quaint and unbelievable ceremony of raising the Medicine Lodge was carried out before our fascinated eyes. Two young bucks were initiated, with strange rituals and chants, into the rite of cutting into strips the hide of a fresh-killed steer, the strips being used to tie the poles of the Lodge together. The weird lulla-lulla-lulling of the squaws, the ordinance of confession to the aged priest with his thin, ascetic face framed in lank black hair above his buckskin robe: the bap‘ism in blood of little children in the arms of their kneeling, grunting mothers: the ceaseless chanting of the old, old warriors of the tribe: the dress parade of the different families—all this we saw and more, one glorious July day.

And the master of ceremonies welcomed the white guests in very good English, going on to pay a glowing tribute to the Stars and Stripes which floated from the peak of the Medicine Lodge and the tepees of the Chiefs. Real patriotism rang in his husky voice when he declared the Indians’ love for this country which was theirs before it was ours. Real love shone

in his somber eyes when he looked up to do homage to Old Glory. It left a lump in my throat, all this— the pathetic clinging of the old folks to their ancient ceremonies and customs, in the face of the utter indifference of the younger members of the tribe. who swarmed uncaring about the little tepee-city on their ponies, waiting only for the baseball game and the races which were to follow.

One impression that lingers after crossing the country is the wonder that Hunger and Want can exist in a world where there are such boundless fields of grain, miles upon miles of it, ready for the harvest: such spreading orchards and vineyards: such herds of cows and sheep, such clover pasturage fragrant in the sun.

And then the boundless spaces yet awaiting cultivation, where tremendous irrigation projects are under way, the great ditches, full to their banks, carrying the snow-water down to the reservoirs; giant pipes banding the mountain sides, defying the desert itself.

And the pioneers are there; they are everywhere. Their lonely habitations dot the prairies and the hills, fair prophecy of that not-far-distant day when there shall be no desert, and the granary of the world shall stretch unbroken across the continent.

At last we were home. The great State of Washington received us. Up and coming is Washington in the March of Empire. Given a fine climate, gorgeous mountains, wide rivers, magnificent forests, tumbling cataracts, she has added the lure of splendid roads to link her busy cities, cities not too busy, however, to be beautiful.

We thought Seattle would be depopulated when we arrived, for a large percentage of the cars we met on the Long Trail bore proudly a Seattle pennant. We grew quite expert at reading license plates as we sped by. “Hello, Seattle,” we would call, or California, or Vermont, Oregon, Maine or Georgia. as the case might be. And they were legion, for America is on the Trail.