Dust, Drought, Depression, and War No. 4

The Dust Bowl, caused by severe drought and a failure to apply dryland farming methods that limit wind erosion of the land, damaged the ecology and agriculture of the American and Canadian prairies beginning in 1934 and displaced about 3.5 million people in the U.S., the largest short period migration in American history. A quarter-million Canadians migrated from the plains.1

The Dust Bowl, caused by severe drought and a failure to apply dryland farming methods that limit wind erosion of the land, damaged the ecology and agriculture of the American and Canadian prairies beginning in 1934 and displaced about 3.5 million people in the U.S., the largest short period migration in American history. A quarter-million Canadians migrated from the plains.1

Before that, and little remembered, was the drought of 1930-1931.

In 1930, dry conditions touched 30 states from the Appalachians to the Rockies, but the brunt of the drought was felt in the lower Mississippi and Ohio valleys. Arkansas was perhaps hardest hit, the epicenter of the disaster. Wells and streams ran dry, crops failed, and by mid-summer, thousands of farm families in the region faced starvation for themselves and their livestock.2

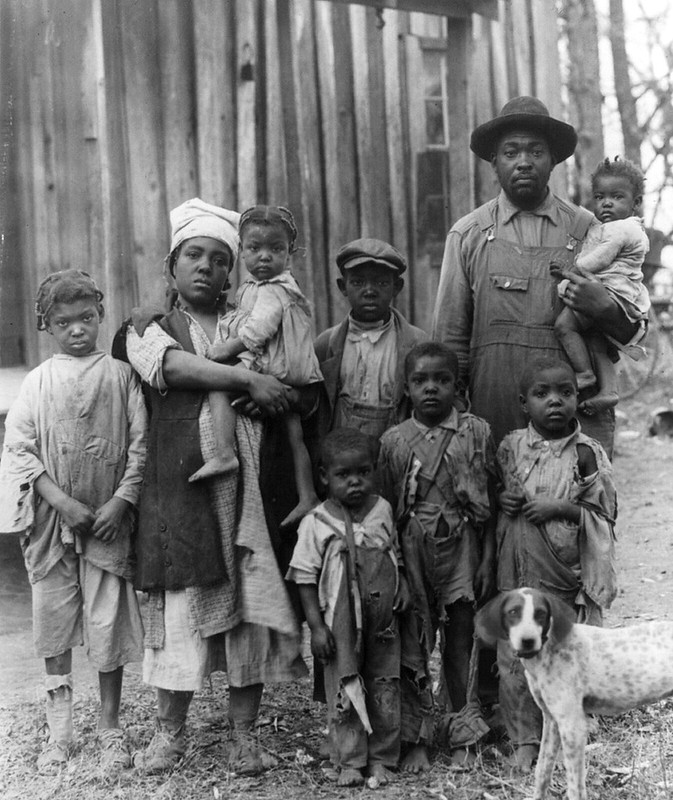

The drought enveloped eight southern states. Of these, it struck southeast Arkansas the worst, striking a region long plagued with poverty and economic instability and where cotton was still king.3 There, unethical practices, racism, and violence kept tenant farmers, day workers, and sharecroppers always suffering and scrambling, always in debt, and always at the mercy of the landowner and the storekeeper.4

The 1929 stock market crash brought ruin to the rich and poor. Bank closings shut off financing and crop prices plummeted as did the need for raw materials.4 The drought just added hunger, illness, and near starvation to the suffering.

Unlike previous droughts that were severe, but short in duration, that of 1930 gradually intensified and lasted for almost a year. With temperatures that reached 113 degrees in some counties, Arkansas lost from 30 to 50 percent of its crops. The parched earth and the famine that followed in its wake came as a final link in a sequential chain of disasters. Like other southern cotton-producing regions, the delta had experienced during the 1920s fluctuating cotton prices, under-production and over-production, indebtedness and foreclosures, an increase in tenantry, and the almost total collapse of the rural banking structure. Natural calamities like the boll weevil invasion and the 1927 Mississippi River flood compounded the region’s serious social and economic ills, for the counties affected most severely by the drought had also experienced the flood. Delta planters and croppers never had an opportunity to recover from one disaster before the depression and drought brought further distress.5

Relief for those affected by the drought was slow and inefficient. President Hoover and other officials were reluctant to provide direct aid, fearing that farmers would end up “on the dole,” reluctant to go back to their work. What aid did arrive was administered locally, usually by representatives of large property owners and employers, a practice that would continue through the New Deal.6

In Arkansas, “The drought relief experience revealed the limitations of local voluntaryism. The individual relief committees consisted of the social and economic leaders of each community — a planter, banker, merchant, and county judge. Rather than administering relief judiciously, the delta committees used discrimination and intimidation to ensure that the labor force remained under their control.”7

On January 3, 1931, angry farmers descended on England, Arkansas demanding food for their hungry, suffering families. Little did they know the drastic changes their future would hold.

The drought ended, but, over the next decade and a half, agricultural production in the south, through mechanization, changed profoundly, convulsing the entire region. Sharecropping and tenant farming shrank rapidly to insignificance through wholesale evictions. Millions of people across the region were displaced to cities or other parts of the country. Mules, symbols and versatile laborers of the soil, became rare. “The southern landscape was depopulated and enclosed; agriculture at last became capital-intensive.”8

- “Dust Bowl.” Wikipedia. last revision July 8, 2021. Accessed August 9, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dust_Bowl.

- Howard, Spencer. “Herbert Hoover and the 1930 Drought.” National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives and Records Administration, September 16, 2020. https://hoover.blogs.archives.gov/2020/09/16/herbert-hoover-and-the-1930-drought/.

- “The Failure of Relief During the Arkansas Drought of 1930-1931.” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Vol. 39, No. 4 (Winter, 1980), pp. 301-313 (13 pages). Accessed August 9, 2021. https://doi.org/10.2307/40024133

- Sonnichsen, C. L. “The Sharecropper Novel in the Southwest.” Agricultural History 43, no. 2 (1969): 249-58. Accessed August 9, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4617663.

- “Tenant Farming in Arkansas.” Southern Tenant Farmers Museum. Accessed August 9, 2021. https://stfm.astate.edu/tenant-farming-history/.

- “The Failure of Relief…”

- Kirby, Jack Temple. “The Transformation of Southern Plantations c. 1920-1960.” Agricultural History 57, no. 3 (July 1983): 257–76. Accessed August 9, 2021. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3742453

- “The Failure of Relief…”

- Kirby